Resilience building at risk? Five key insights for addressing borderless climate risks

Introduction

Borderless climate risks have the potential to severely hamper or completely roll-back progress made on building resilience through climate change adaptation. Can they be addressed in the follow-up of the Paris Agreement’s global goal on adaptation?

This concern was the convening force behind a recent UNFCCC Side Event at COP23, titled A Global Adaptation Goal and borderless climate risks: Strengths and limits of the Paris Agreement. The event was co-organized by SEI, Acclimatise, and the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, and was supported by both Formas and Mistra Geopolitics. Below are five key insights from the conversation, which brought together researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers.

1. Transboundary and teleconnected risks

Traditionally, climate risk is closely linked to the direct impacts of climate change, like increased flooding or drought, heat waves, or other extreme weather events. Yet, according to Magnus Benzie, SEI Research Fellow, this view makes several critical omissions. “By focusing primarily on climate impacts within national borders, both policy-makers and researchers have tended to overlook the ways that climate change in one part of the world can affect people in another,” Benzie said.

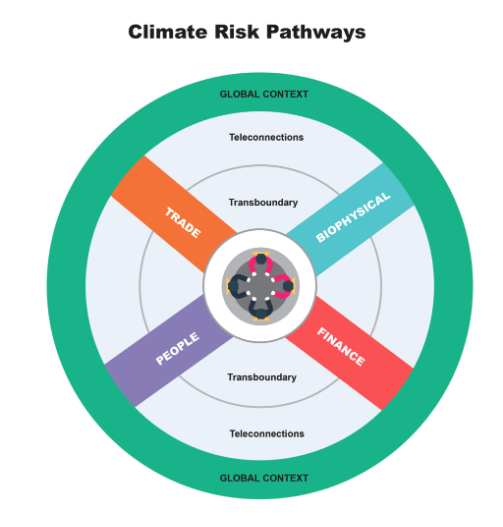

Climate impacts can flow across borders via several different ‘pathways.’ These include shared biophysical flows like shared rivers or ecosystems, trade flows, financial flows like investment, and flows of people as patterns of mobility, migration, and tourism change. Importantly, these borderless climate risks do not always occur among neighbours; transboundary risks may inspire regional cooperation when the impacts are localized, but risk can also be teleconnected, linking countries and people relatively far away from one another.

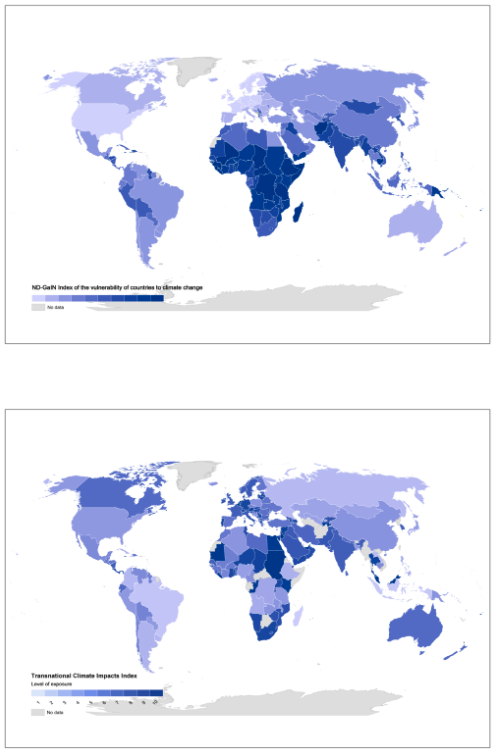

By considering the borderless dimensions of climate impacts, we are presented with a quite different view of vulnerability to climate change, raising important questions for the way we adapt, both nationally and as a global community.

2. Adaptation as a global public good?

Throughout the conversation, a potent and recurring example was rice trade between exporting countries like Thailand, Vietnam and India, and heavily import-dependent countries like Senegal. Extreme weather events that impact rice exporters like Thailand cause price hikes, which makes food security in Senegal vulnerable to climate impacts beyond its own borders. Taking trade relationships like these as a focus, Oliver Schenker, from the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, argued that climate adaptation should be considered a global public good with important benefits for both importers and exporters.

Using economic modelling, Schenker’s work suggests that when developing countries receive adaptation finance and are able to optimize their adaptation, the benefits are felt all across the globe. There is a collective interest in financing adaptation, a statement strongly seconded by panellists Mizan Khan, a climate finance negotiator from Bangladesh, and Maria Banda, on the faculty of law at the University of Toronto.

3. Borderless climate risks under the Paris Agreement

Recognizing the potentially significant role of borderless climate risks, as well as the collective interest in addressing them, what provisions or instruments exist under the Paris Agreement to help take these into account? According to Annett Möhner, Team Lead for the Adaptation Committee at the UNFCCC Secretariat, National Adaptation Plans may be one potential avenue for beginning to identify and assess borderless climate risks. Some countries have already begun to do this, though teleconnected risks are rarely considered. Additionally, as methodologies are developed for assessing progress toward the Global Goal on Adaptation and performing the Global Stocktake in 2023, there is an opening to raise awareness about these risks, and think about how they may be meaningfully incorporated into stocktaking efforts.

Likewise, as Åsa Persson, Senior Research Fellow at SEI noted, addressing borderless climate risks necessarily intersects with discussions about climate adaptation finance, and there is a need to think carefully about how to manage these risks while not re-allocating resources away from countries vulnerable to direct climate impacts. Dustin Schinn, Climate Change Specialist at the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), agreed, and suggested that countries needed to be in the “driver’s seat” for addressing borderless climate risks, and should be supported by finance and global coordination.

4. Not the only game in town

Given the country-driven nature of the Paris Agreement, it is also important to consider that the UNFCCC may not be the only venue for capturing and addressing borderless climate risks. Despite Senegal’s interest in bolstering Thai rice production, adaptation must be country-driven and Thailand may rightly choose to focus on other adaptation priorities of national importance.

Rebecca Nadin, head of the Risk and Resilience Programme at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), suggested that there is the potential to learn from other UN conventions like the UN Convention to Combat Desertification or the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, or to mainstream climate considerations into the multitude of existing water resources treaties. Similarly, Sara Venturini, Policy Analyst at Acclimatise, argued that trade agencies, financial institutions, and private sector actors may have a substantial role to play in this regard, especially given their high capacities for complex risk assessment.

5. Research for the future of borderless climate adaptation

Moving forward, there is a strong call for more knowledge and research in this area. It is especially necessary to develop methodologies, indicators, and indices to raise awareness about the potentially significant impacts of borderless climate risks, especially those that are teleconnected. Strong calls were made to produce specific case-studies, as well as to develop meta-analyses that locate commonalities, help to identify best-practices, and foster collaboration.

This sentiment is perhaps best captured by John Firth, CEO at Acclimatise, who during the panel discussion remarked: “climate change has caused us to embark on a complex experiment that we do not entirely understand. New teleconnections may arise as we continue to grapple with how we should adapt to our changing world – work in this area will need to be iterative and ongoing.”

Comments

There is no contentYou must be logged in to reply.