New risk horizons: Sweden’s exposure to climate risk via international trade

Introduction

This study focuses on Sweden and its place in the global trade system. The objective was to develop innovative multi-method approaches to identify and assess transboundary climate risks facing Sweden via its international trade links.

Sweden is projected to experience direct impacts from climate change as a result of changing temperature, precipitation and weather patterns within its borders. However, due to its relatively high levels of wealth, social cohesion, institutional stability and other factors, Sweden is generally thought to be well-placed to adapt to these direct impacts and therefore ranks among the least vulnerable countries globally.

Transboundary climate risks, on the other hand, pose an altogether different, more complex challenge. Due to the openness of its economy and society, its position “high up” in the global value chain and its reliance on imports and exports to support consumption and jobs, Sweden is likely to be highly exposed to climate risks that originate in other countries, especially via trade. This “external” dimension of Sweden’s climate vulnerability has been largely ignored until relatively recently, due partly to the lack of established tools for identifying and assessing such risks. That is why the study sets out to develop and test multi-method approaches for assessing national-level exposure to climate risk via trade.

The report is structured as follows:

- Section 1 introduces the background to the research and offers a short justification for the focus on national-level exposure.

- Section 2 reviews the state of the art and describes the data that are used in the study. It then introduces the multi-method approaches in detail.

- Section 3 provides results for both approaches; detailed descriptions of methodological steps and choices are offered in Appendices 1–6.

- Section 4 offers a discussion of the success and limits of the multi-method approaches, and offers a few reflections for future research.

- Section 5 summarizes the authors’ reflections on the policy implications of the study, and offers four recommendations for actors based in Sweden.

- Section 6 provides conclusions for the report as a whole.

This article is an abridged version of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text.

Method

This study introduces and provides results for two multi-method approaches for assessing national-level exposure to climate risk via trade:

- The first analyses Sweden’s trade interactions with the rest of the world using three distinct sets of trade data.

- Each type of data emphasizes different levels or tiers of Swedish trade; each has strengths, but also limitations, for the purpose of assessing transboundary climate risk. National toll logs – traditional trade statistics – give accurate and timely information about the first tier only (i.e. direct imports from “the last port of call”); so-called “input-output” tables can be used to trace the “value added” to consumption at stages in the supply chain, but with an emphasis on the higher tiers; and resource footprints provide insights on the initial material input to supply chains in the lowest tiers (e.g. land or water inputs).

- The authors develop a method for combining data on climate risk in other countries with these three classes of trade data to compare the insights generated by each.

- The second approach focuses on a particular Swedish supply chain: soy from Brazil.

- Soy has rapidly become a key commodity for Swedish consumption because of the role it plays as animal feed and an oil crop in various forms of meat and dairy and processed food production. And it is not only Sweden that has developed a love for soy. Countries at various levels of development now depend on imported soy in ways that few people realize. If climate change affects the availability and price of soy, consumers around the world will feel the effects on the cost of their weekly food shop; food and drink businesses will suffer and traders and governments will enter a costly and uncertain struggle to secure access to soy imports.

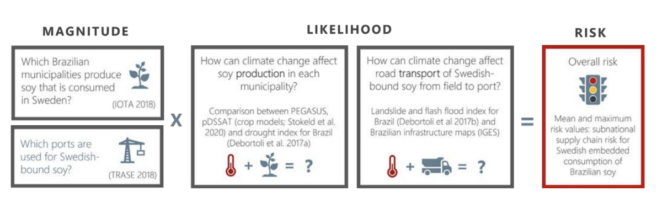

- The authors therefore pioneered an approach to assess supply chain climate risk using the best available data at the highest level of granularity possible. This resulted in a mapping of climate risks to soy production at the municipality level throughout Brazil, which is then traced all the way through international supply chains to identify embedded soy in Swedish consumption.

- In addition, they developed a method to assess the risks that climate change poses to the transport of this soy from farm to port in Brazil, recognizing the importance of climate change “choke points” on supply chain logistics – a dimension that is rarely included in climate risk assessments of trade.

These two approaches constitute a significant innovation in multi-method assessments of transboundary climate risk. They combine to raise important new insights and questions for adaptation policy and global governance more generally. They reveal a category of climate risk that, today, is not governed by anyone.

Learn more about the two methodological approaches, as well as the key methodological challenges, on pages 11-20 of the report.

Key Messages

This study finds that traditional approaches provide a relatively reassuring picture, highlighting the dominant role played by geographically close trading partners (Germany, Nordic countries) whose climate vulnerability is among the lowest globally. Beyond this first tier, Sweden largely trades with EU countries and other relatively low-vulnerability markets.

However, more nuanced trade data reveal Sweden’s previously hidden links to much more vulnerable countries that play a critical role in Swedish supply chains, particularly emerging economies in Asia and Africa. These revelations add up to a new risk horizon for Sweden; global climate change threatens the stability and availability of inputs to Swedish consumption that first enter our supply chains thousands of miles away in higher-risk countries. Key trading partners in lower tiers of our supply chains play an important role in the Swedish economy and yet they have existed in a statistical shadow, meaning their influence on our own climate vulnerability has not been appreciated, until now.

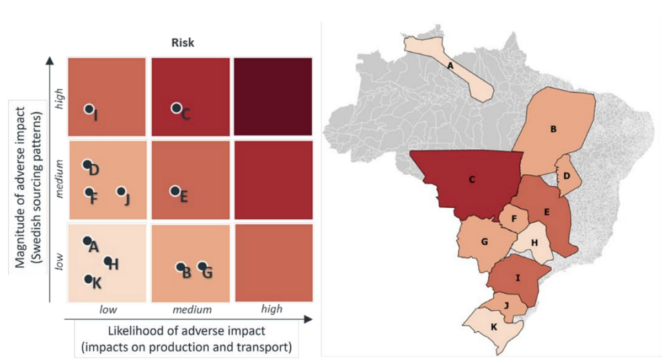

The results of the second approach show that Swedish sourcing patterns of Brazilian soy are connected to areas of relatively low risk of impacts of climate change along the supply chain. The majority of Swedish sourced soy from Brazil derives from the vicinity of the state of Mato Grosso (area C), an area predicted to be at very low to low risk of drought and crop yield losses in the future. The high likelihood of adverse impact in this area is related to transport risk. Road transport from the area entails long and underdeveloped roads with medium to high risk of landslide and flash floods along the way and few alternative routes to port. The area is, however, a hotspot for ongoing developments in alternative infrastructure, such as waterways in the Amazon, which the method does not take into account. Thus, the significance of the future transport risk to this area should be carefully interpreted, based on future infrastructure development.

Learn more about the study’s results and insights gained from the methods on pages 22-36 of the report.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The results of the study can be used to motivate a new generation of adaptation planning – one that engages with the challenging reality of risk in a globalized world. Two overarching conclusions stand out:

- There are limits to substitutability in volatile systems because climate change is a risk driver that will be occurring everywhere at once; the number of vulnerable lower tier trade partners and the “stickiness” of certain trade links imply that substitution in practice may not be as feasible an adaptation response as is often assumed.

- Systemic risk is subtle and hard to measure, especially when relying on traditional statistics and methods. While seemingly well-insulated from climate risk via resilient “top tier” trade partners, Sweden is exposed to cascading systemic risk because of its deeply embedded position high in the value chain. In a world experiencing extreme climate change, this level of climate risk may reach toxic proportions.

Together this constitutes a new risk horizon for Sweden. But Sweden is well placed to push forward as a pioneer in this new adaptation landscape.

Policy recommendations:

In light of the transboundary risks identified in this study, the researchers offer the following recommendations to Sweden-based actors:

- Initiate dialogues on adaptation to transboundary climate risk with economic sectors in Sweden

- Focus on transboundary climate risk in the next iteration of the National Adaptation Strategy

- Expand the remit of the Swedish National Knowledge Centre for Climate Change Adaptation to address transboundary climate risk

- Engage in climate diplomacy to build systemic resilience to transboundary and systemic climate risk

To explore the policy discussion and recommendations, and the study’s overall conclusions in more depth refer to pages 32-43 of the report.

- Nordic perspectives on transboundary climate risk

- Four ways to step up environmental ambitions during Sweden’s EU presidency

- Contesting legitimacy in global environmental governance - An exploration of transboundary climate risk management in the Brazil

- Impacts of climate change on global food trade networks

- Climate risks to trade and food security: implications for policy

- Dispatch from the Climate-Trade Nexus

Comments

There is no contentYou must be logged in to reply.