The Story of Water in Windhoek: A Narrative Approach to Interpreting a Transdisciplinary Process

Introduction

The use of narratives to present the stories of events or issues is becoming more prevalent in urban climate research, as they provide an understanding of urban issues as a form of evidence that is accessible to practitioners and civil society. Furthermore, they help to capture the range of voices necessary to understand complex problems.

The aim of the paper is to present a story about the 2015 to early 2017 Windhoek drought in the context of climate change while using the narrative approach. The story that is presented here is derived from the engagement of participants in a transdisciplinary, co-productive workshop, the Windhoek Learning Lab 1 (March 2017), as part of the FRACTALResearch Programme. This paper aims to understand the contested nature of water that is present in the narrative or ‘story’ of the water problems and challenges in the city of Windhoek in the context of climate change.

This paper first presents an overview of the concept of the ‘narrative’ and how it has been used in previous qualitative research as a form of policy analysis. In the contextual section, the FRACTAL project is outlined with a focus on the importance of the transdisciplinary City Learning process in the project. The qualitative method of undertaking a narrative analysis is then presented. The discussion and results of the narrative analysis are presented in the last section.

To learn more about the initial and developing hypotheses that CRNs are useful in communicating and integrating knowledge on climate risk, their application as boundary objects, their limitations and caveats, and recommendations on their application, read this article. This article highlights the use of CRNs in Windhoek, examining the development of CRNs and their implementation into decision-making processes. This article focusses on the feedback from a few city researchers on their narrative processes. Finally, the FRACTAL podcast describes the CRN process in great detail – access the podcast here.

Literature Review of Narratives

People use ‘story-telling’ as a means of making sense of complex phenomena and thus it is argued that narrative analysis is an important method of analysing these stories, their production and their influence at different scales.- Fløttum et al. describe a narrative as a text or discussion with a ‘storyline’, which helps to identify the characters or actors in the story, namely, the hero, the victim, and the villain, and their relationships.

- In a narrative, the storyteller can “give the floor to others” where alternative narratives are included.

- Fløttum et al. argue that a policy narrative has the structure of a story.

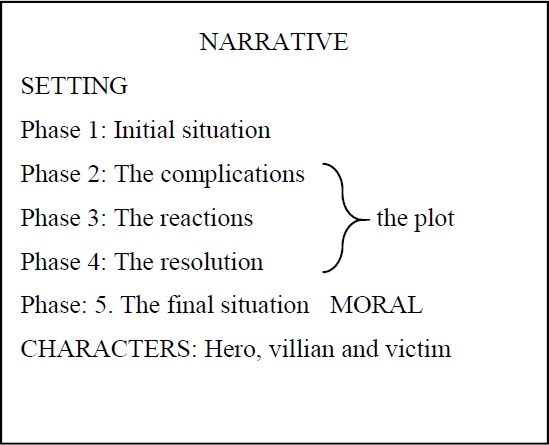

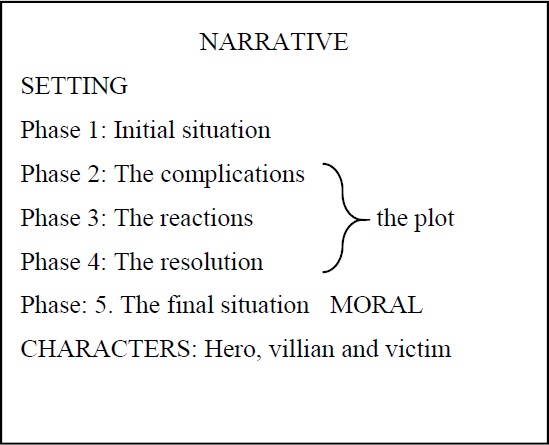

Phases of a narrative

- The initial stage of the story telling sequence presents the intrigue and tension between different actors and events at the outset of the story, which describes the conditions that determine the initial situation.

- The complication is part of the plot and describes problem or issues experienced in the specific context and related to certain actors and events.

- The reactions as the next stage, refers to certain “recommendations or reactions”, which should take place to address the problem.

- The resolution is what is decided should be done about the problem or complication.

- The final situation is an argument that explains the reactions and why they were made, often providing a moral justification.

The Context of Water in Namibia and Windhoek

Windhoek has always experienced a shortage of water and has strived to combine surface water and unconventional sources of water to supply the water demand of the city and its surrounds.

Windhoek’s climate, status as capital, economic importance, and demographic growth provide an important context in which to understand the story of water in the city of Windhoek.

- The Grootfontein-Omatako catchment in the Central Area of Namibia (CAN) forms the main water supply system for the city of Windhoek and surrounding areas.

- The potable water supply scheme is owned, operated and maintained by NamWater as the national bulk supplier of water in the country

- The CoW (Department of Infrastructure, Water and Technical Services) is responsible for the supply, distribution, and quality of potable water within the urban area.

- The Ministry of Agriculture, Water, and Forestry (MAWF), the Namibia Water Corporation (NamWater) and the CoW are the main institutions governing the supply of water to Windhoek.

The problem at this stage is the shortage of surface water and the reliance on unconventional sources of water where CoW has partnered with private sector to reclaim water.

The region experienced extreme drought in 2015 and early 2017, which has put pressure on the CoW to provide water for Windhoek.

Windhoek Learning Lab

A Learning Lab is an event that is a platform of engagement and collaboration in which participants from the city discuss and identify critical issues and share knowledge and potential solutions in relation to burning issues with members of the FRACTAL team.

Participants collaboratively identified the two burning issues of: (1) water insecurity; and, (2) lack of access to services in informal settlements, including water and the related actors.

The Windhoek Learning Lab Report is the major source of data for the paper,

The Story of Water in Windhoek

This section presents the ‘narrative of water in Windhoek’ through the five stages of the narrative. For more details, please refer to the publication.

Initial Situation

- The participants of the Learning Lab identified ‘drivers’ that contributed to the precariousness of the city’s water supply. These drivers were proposed to have led to the following problems: limited water supply (drought); disruption of livelihoods; compromised health and hygiene; the unequal distribution of water among residents; and, the loss of income due to unemployment and retrenchment.

- The drought had reached crisis levels where the water demand increasingly exceeded the supply in the face of the drought. The City of Windhoek (CoW) was unable to address the problem, particularly the recharging of the Windhoek aquifer due to lack of funding.

- The MAWF, NamWater and CoW are the primary decision-making actors that made the major management decisions at different stages of the drought.

- The main private sector actors that were affected and involved in the drought were water dependent businesses.

Complications

- Drought, and increased water demand in relation to constrained water supply were the critical context-specific issues affecting water security in the city. The burning issue was therefore conceptualised as ‘water insecurity’ in the city without any interrogation of what this meant. A complication was that this understanding varied among actors.

- Climate change was also a recurring theme in explaining water challenges. While it was agreed that the impacts of climate change were apparent in the city manifesting in droughts, uncertainties remained as to how to act at the city-regional scale to provide some solutions to this issue.

- As actors struggled to agree on remedial action on the water challenge, the MAWF government was pointed to as both the ‘villain’ and ‘hero’.

- There was a history of contention over the responsibility to provide solutions for water shortages, even before the drought began.

The Reactions to the Water Shortage and Drought

The four main reactions to drought and water shortage in Windhoek, which had been undertaken by the time of the 1st Learning Lab:

- The City of Windhoek put in place the Water Demand Management (WDM) Strategy and the Drought Response Plan (DRP) to avert critical water shortages and managing water supply and water use during drought situations.

- In 2016, the CoW launched a public water saving campaign “Save Water” to urge residents to save 40% of their water consumption.

- The aquifer was identified by the national government and a Cabinet resolution directed that it be a protected zone.

- A national Cabinet Committee on Water Security was formed, which is currently discussing inter-basin transfer

The narrative of the shortage of water also included what could potentially be done to address the issue of drought.

Final Situation

- The national government instructeds NamWater to provide the funds for CoW to complete the recharging of the aquifer, which supplied water to the city at the last minute at the end of 2016. This showed the lack of decentralization of water governance in Namibia.

- The drought has been a critical trigger to place climate change on the agenda of CoW and raise awareness amongst all the stakeholders in the city about water security.

- The final situation of the story is that ongoing collaborative work by CoW with FRACTAL on the city’s burning issues is planned to integrate climate change into future decision making for the longer term.

Main learnings

The main learnings from this paper are twofold.

- The first is that what we have found confirms literature that reports that decentralization is weak in southern African cities with national governments retaining decision-making power and resources in relation to water and energy.

- However, the evidence shows that the CoW has been proactive and innovative in its approach to securing non-conventional water sources, despite the lack of response of the national government to its repeated requests for financial support.

- The second lesson is that the application of the narrative approach to a participatory process provides a lens to make clear the actors who were involved in the process and the events that occurred during the crisis of the drought.

- Participant observation showed powerful actors steering the debate and dominating discussions on occasions, hence influencing the storyline of the narrative: this is a critical challenge.

- This challenge calls for a revisiting of the design and content of participatory, collaborative workshops to more successfully ‘equal the playing fields’ among actors.

Related resources

- FRACTAL: Future Resilience for African Cities and Lands

- Dialogue for decision-making: unpacking the ‘City Learning Lab’ approach

- Embracing the uncomfortable silences in climate information exchange

- Receptivity and judgement: expanding ways of knowing the climate to strengthen the resilience of cities

- Ensuring Future Water Security through Direct Potable Reuse in Windhoek, Namibia

- Inspiring Climate Action in African Cities

- Drought and its interactions in East Africa

- Bottom-Up Innovation for Adaptation Financing – New Approaches for Financing Adaptation Challenges

- Climate Change at the City Scale

- Learning Labs in Windhoek: creating collaborative ways to address climate change in African cities

- "Explainer" Guide: Co-exploring Terminologies

- City to city learning and knowledge exchange for climate resilience in southern Africa

- Ensuring Future Water Security through Direct Potable Reuse in Windhoek, Namibia

- Using stories to encourage action

- Co-producing climate information for Windhoek decision making

- Climate risk narratives: An iterative reflective process for co-producing and integrating climate knowledge

- FRACTAL Podcast Series - Exploring transdisciplinary approaches to support resilience and adaptation decision making

- Climate narratives: What have we tried? what have we learned? What does this mean for us going forward?

(0) Comments

There is no content