Local costs of conservation exceed those borne by the global majority

Introduction

Cost data are crucial in conservation planning to identify more efficient and equitable land use options. However, many studies focus on just one cost type and neglect others, particularly those borne locally.

This study*develops, for a high priority conservation area, spatial models of two local costs that arise from protected areas: foregone agricultural opportunities and increased wildlife damage. This study then maps these across the study area and compare them to the direct costs of reserve management, finding that local costs exceed management costs. Whilst benefits of conservation accrue to the global community, significant costs are borne by those living closest. Wherelivelihoods depend upon opportunities forgone or diminished by conservation intervention, outcomes are limited. Activities can be displaced (leakage); rules can be broken (intervention does not work); or the intervention forces a shift in livelihood profiles (potentially to the detriment of local peoples’ welfare). These raise concerns for both conservation and development outcomes and timely consideration of local costs is vital in conservation planning tools and processes.

This open access paper was published inGlobal Ecology and Conservation in April 2018.You can access the full publication here. A summary of the key findings is provided below. See the full publication for more details. This paper is made available under a Creative Commonslicense.

Methods

Study area

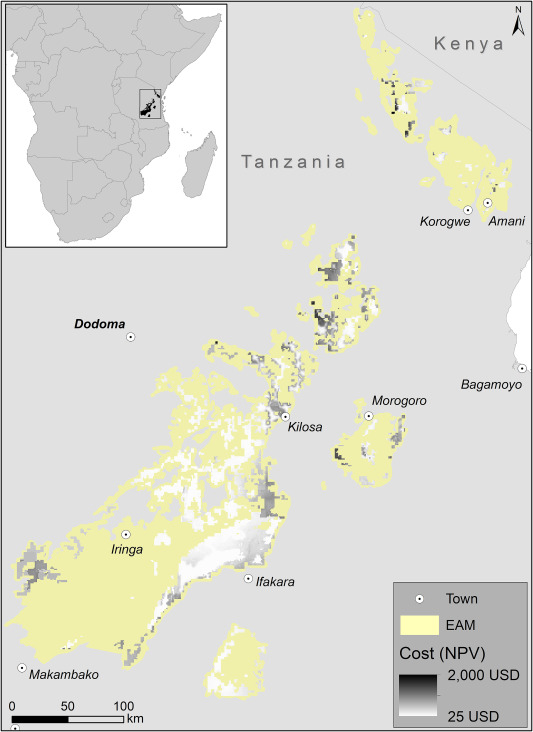

The Eastern Arc Mountains (EAM) in Tanzania support tropical moist forests with exceptionally highspecies richness and endemism.

To understand how the costs of conserving a tropical biodiversity hotspot are distributed, we compare subnational spatial models of three conservation costs that vary in their distribution from local to international. In the EAM the direct costs of reserve management, borne nationally and internationally, have been modelled spatially. We also develop models for opportunity cost and damage costs, which villagers living adjacent to reserves elsewhere in Tanzania considered the most important local costs.

Yield data

We use estimated yields of maize and beans across East Africaunder current farming practices for sowing time, planting density and application.

Farmer survey

During August-October 2009, we surveyed 135 farmer households from 23 villages. We collected information on planted crops, yields, prices, and labour. We also asked whether the farm experienced crop damage and, if so, the species causing the damage, its frequency and extent, and the measures taken to guard crops.

Opportunity costs of reserves

The opportunity cost of reserves is calculated from the most likely profitable alternative if the land were not conserved. Where market data are unavailable, land price can be estimated from the expected net present value of future profits from the land, which will vary across space, reflecting changes in land quality and transportation costs.

The opportunity cost of land is calculated from its net agricultural and charcoal value multiplied by the probability that it will be converted. Thus we calculate the expected net value (bounded between zero and the expected rent from the land if it were converted immediately), rather than the potential net value.

Wildlife damage costs of reserves

The most consistently reported predictor of damage by wildlife in Tanzania and elsewhere is distance to reserves. Therefore, we estimated damage costs using work by that was conducted in parts of East Africa with similar farming techniques and damaging species to those found in our study area.

Key findings

- Across the EAM, opportunity cost varies substantially, with estimates for a medium discount rate (r = 15%) ranging from 0 to 1336 USD/ha (mean = 191 ± 234SD).

- Opportunity costs are greater near mountain bloc edges, where population densities and accessibility are higher, resulting in a greater probability of conversion.

- Although the value of charcoal stocks andagricultural yields are greater in forest, forest is converted at far lower rates than woodland, resulting in expected opportunity costs for forest that are substantially smaller than those for woodland.

- The mean wildlife damage cost of forest and woodland is far lower than our estimated opportunity costs, at just 9.3 USD/ha, in part because of the many areas of forest and woodland that do not border cropland.

- However, this varies widely and is highest in the centre and northeast of the study area, where high value cropland borders forest and woodland habitat.

- Management and opportunity costs are greater near more populated and accessible areas, while damage costs are associated with cultivated areas.

- Across the entire study area, opportunity and management costs are roughly equal for forest cells, accounting for 44% each of the total cost, whilst damage costs account for 12%.

Lessons Learnt

- The reported costs, and underfunding, of biodiversity conservation has focused largely on management costs; locally borne costs have received less attention.

- Protected areas are a vital component of conservation efforts, yet unless those living closest to a resource receive benefits that are equal to or exceed the cost that they bear under conservation, the system is likely to be less effective from either conservation or development perspectives.

- Where livelihoods depend upon opportunities forgone or diminished by conservation intervention, outcomes are limited.

- Activities can be driven elsewhere, so displacing threats, rather than removing them; the rules can be broken, reducing the effectiveness of the conservation strategy; or the conservation intervention forces a shift in livelihood profiles, potentially to the detriment of local peoples’ welfare.

- All of these raise concerns for both people and wildlife and timely consideration of the magnitude and distribution of local costs in the conservation planning process is, therefore, vital.

(0) Comments

There is no content