Transnational climate change impacts: An entry point to enhanced global cooperation on adaptation?

Introduction

The Paris Agreement recognizes adaptation to climate change as a “global challenge faced by all, with local, sub-national, national, regional and international dimensions”, and a key component of the global response needed to protect people, livelihoods and ecosystems.

Article 7 of the agreement thus sets a global goal on adaptation, and calls for international cooperation and support to enhance adaptation action. Within countries, it encourages the development of national adaptation plans and priorities for action, as well as periodic adaptation communications under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The language of the Paris Agreement reflects a growing understanding that while the physical impacts of climate change are location-specific, in a globalized world, people and countries are increasingly connected. This means adaptation is ultimately a collective endeavour: we are all in this together.

Applying this insight to adaptation planning requires a new lens through which to view climate impacts and adaptation responses. This policy brief, which builds on an SEI Working Paper published earlier this year, introduces a framework for quantitative assessment of country-level exposure to what we call the transnational impacts of climate change.

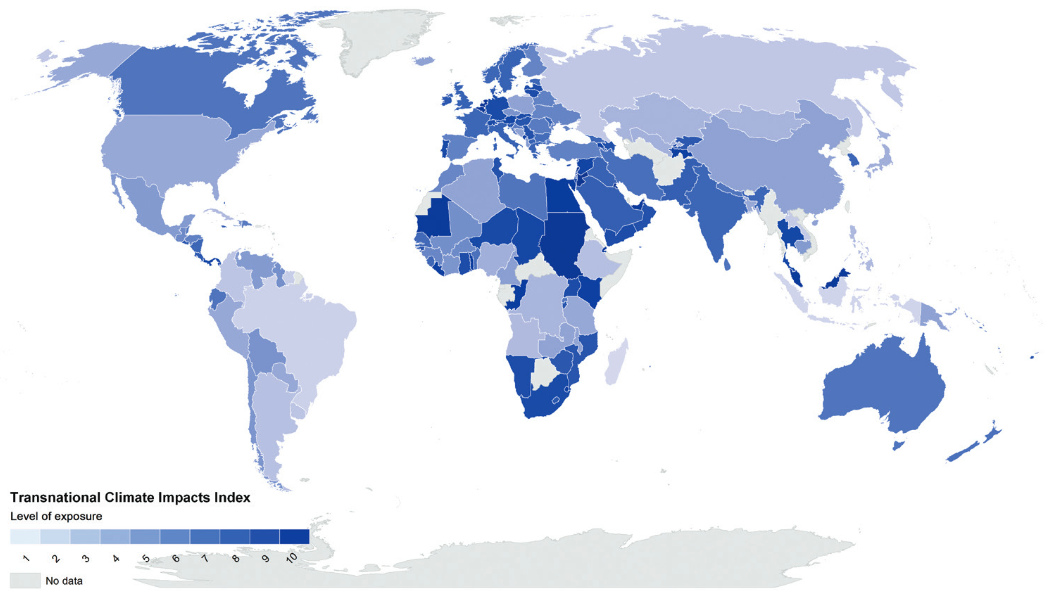

Transnational climate impacts reach across borders, affecting one country – and requiring adaptation there – as a result of climate change or climate-induced extreme events in another country. We have used our analytical framework to develop nine indicators of country-level exposure and a composite index: the Transnational Climate Impacts (TCI) Index.

This brief*explains how the indicators and the TCI Index were developed, describes some of the results, and offers reflections on the implications for both national adaptation planning, and global cooperation on adaptation under the UNFCCC.

*Download the full text from the right-hand column. The sections below provide an overview only – please see the full text for much more insight.

The Transnational Climate Impacts Index

We identify four main transnational risk pathways: The biophysical pathway encompasses transboundary ecosystems such as river basins, oceans and the atmosphere. The finance pathway represents capital flows and climate impacts on assets held overseas. The people pathway involves the movement of people between countries, from tourism to migration. The trade pathway transmits climate risks within regional and global markets and across international supply chains.

To assess these 9 indicators were developed:

- Indicator 1: Transboundary water dependency ratio

- Indicator 2: Bilateral climate-weighted foreign direct investment

- Indicator 3: Remittance flows

- Indicator 4: Openness to asylum

- Indicator 5: Migration from climate vulnerable countries

- Indicator 6: Trade openness

- Indicator 7: Cereal import dependency ratio

- Indicator 8: Embedded water risk

- Indicator 9: KOF Globalization Index

The Index is a simple composite index that combines the results from each indicator. They are unweighted, as we have found little justification for giving more or less weight to specific indicators at this stage. A total of 203 countries are included in the analysis, coded by the ISO325 standardized country codes. The index maps use the Robinson map projection and have been created in ArcGIS software. The data are from the years 2007–2013. Figure 2 visualizes the results (see above).

For an in-depth account of the methodology behind the TIC Index read “Introducing the Transnational Climate Impacts Index: Indicators of country-level exposure – methodology report“.

Key Messages

-

In an increasingly globalized world, no country is fully insulated from the impacts of climate change outside its borders. This means we need to rethink assumptions about which countries are vulnerable to climate change, and carefully consider how climate risks are transmitted across borders.

-

The Transnational Climate Impacts (TCI) Index presented in this brief shows that many countries that do not rate as “particularly vulnerable” to direct climate change impacts are highly exposed to transnational risks: for instance, the Benelux countries, Germany, and the Scandinavian states.

-

Since globalization is a key factor in transnational climate risks, less-developed economies may score lower on some TCI indicators. However, several factors can lead to higher TCI scores, such as being a small country (e.g. the Gambia, Fiji), landlocked (e.g. Tajikistan, Swaziland, Armenia, Mauritania), and highly trade-dependent (e.g. Malaysia and Thailand). The four highest-scoring countries are in the Middle East: Jordan, Lebanon, Kuwait and United Arab Emirates.

In the context of the UNFCCC, and more broadly in international cooperation, this means it makes no sense to identify one set of countries as “climate-vulnerable” and the others, presumably, as unaffected, but perhaps willing to provide adaptation finance out of sheer generosity. Our analysis shows that even wealthy countries with no significant physical exposure to climate change impacts could face serious economic and social repercussions from impacts elsewhere. Working together to enhance adaptation is in the interest of all countries that want to do well in a globalized world.

Another important insight from this work is that countries developing national adaptation plans need to look not just at risks within their own borders, but also at the transnational pathways that may expose them to further risks from climate change impacts abroad.

Policy Recommendations

-

As the Parties pursue and build on the global adaptation goal set in the Paris Agreement, they should recognize the transnational dimension of climate impacts and the global benefits of adaptation. This could help to secure all Parties’ participation in an effective adaptation regime.

-

Countries should address transnational climate impacts in their national adaptation plans, and consider opportunities for international cooperation to address shared risks. Regional approaches to climate impact assessment and adaptation planning could be very valuable. Cooperation among trade partners is also crucial.

-

Adaptation finance needs to be scaled up significantly, under the UNFCCC and beyond. Industrialized countries need to recognize that climate change will heighten systemic risks to the global economy; global resilience can be achieved by ensuring that all countries have the resources and capacity to adapt. International adaptation finance is an investment in global economic stability.

-

Donors should explicitly design programmes and finance mechanisms to address transnational climate impacts, including via multi-country projects. Donors should take care not to engage in “strategic adaptation financing”, however, that only seeks to reduce their own exposure to risks abroad. Equity and vulnerability considerations should guide the distribution of climate finance.

-

Adaptation communications under the UNFCCC should, among other things, serve the function of climate risk disclosure at the country level. For this, they need to include: a summary of key climate impacts; an outline of planned adaptation responses; a screening of likely in-country adaptation gaps or relevant limits to adaptation; and a brief assessment of how impacts and adaptation effects might spill over to other countries. Parties should see a mutual benefit of providing such information in formats that can be easily digested and compared by other interested countries.

-

The global stocktake, as agreed in Paris, should effectively assemble this information into an easily comparable registry of national risks and activities so that countries can more easily survey and assess the consequences to them of climate change in other countries. The global stocktake should also consider the global dimensions of climate risks every five years.

-

The Adaptation Committee, in fulfilling its role to “ensure the coherence” of global adaptation, should specifically aim to assess where adaptation gaps or maladaptation at the country level may create systemic global risks or transnational impacts for other countries. All bodies involved in adaptation governance and international cooperation should reconsider their strategies in light of such information.

Related resources

- Read the Transnational Climate Impacts Index: Indicators of country-level exposure methodology report

- Read the SEI discussion brief: Adaptation without borders? Understanding indirect climate change impacts

- Read the SEI Policy Brief: National Adaptation Plans and the indirect impacts of climate change

- Explore the Adaptation without Borders - Indirect Impacts of Climate Change theme on weADAPT

- Read more about the project Adaptation without Borders on SEIs website here

(0) Comments

There is no content