The Global Transboundary Climate Risk Report

Introduction

As their name suggests, transboundary climate risks do not respect national or international borders. They are being triggered by climate change and by our adaptation responses to that challenge. A climate hazard in one country may well have an impact that crosses national borders to affect its neighbours. In our interconnected world, however, its impact may also jump across entire regions and vast oceans to harm distant countries. From flooding in Bangkok that disrupts global industrial production, to the spread of diseases that hold back economies, transboundary climate risks are an immediate threat to our collective wellbeing. And they hinder the prospects of achieving global goals on climate adaptation.

Transboundary climate risks also include those transmitted by adaptation responses. While these responses can have positive results across borders and deliver shared benefits, they can also redistribute or even increase (rather than reduce) the risks, by shifting them to other countries, sectors and communities. This happens, for example, when countries impose export bans to protect domestic markets from food price shocks, which can turn a local shock into a global food crisis.

This report by Adaptation Without Borders rings the alarm bell on transboundary climate risks. It is the first collection of evidence on risks that undermine effective responses to climate change, yet that remain largely unrecognized: a ‘blind spot’ in both climate policies and solutions. It brings together the best available knowledge, drawing on a wealth of case studies.

The report is structured as follows:

- Part I: The state of knowledge on transboundary climate risks (p.17-28)

- Part II: Assessing 10 globally significant transboundary climate risks (p. 29-96)

- Part III: The solution space to managing transboundary climate risks (p. 97-113)

This article is an abridged version of the original text, which can be downloaded from the right-hand column. Please access the original text for more detail, research purposes, full references, or to quote text.

Building the evidence base: 10 globally significant transboundary climate risks

This report is unique in drawing on a series of case studies to explore 10 transboundary climate risks of global importance. The assessments take a deep dive into how transboundary climate risks impact local livelihoods, and critical sectors such as finance, health and global supply chains (e.g. agricultural commodities and manufacturing components). Each chapter explores, for a given transboundary climate risk, its likelihood in a changing climate, its impacts across different distances and time scales, and its method of transmission, as well as provides readers with an in-depth analysis of a representative real-world case study.

Transboundary climate risks explored in the report:

- Terrestrial shared natural resources:Chapter 2.1 assesses transboundary climate risks in shared river corridors in mountain regions that are facing increasing risks of melting glaciers, flood disasters and cross-border risks to infrastructure, energy distribution and livelihoods.

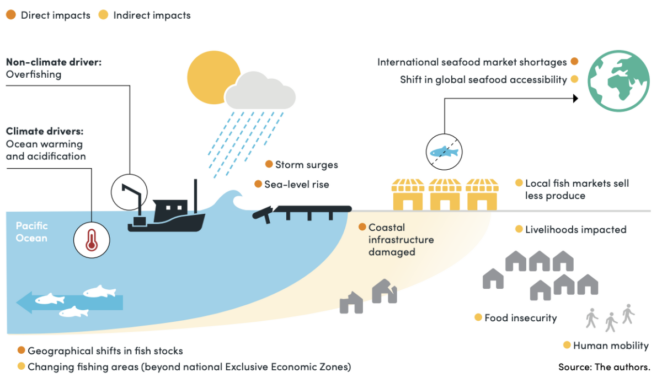

- Ocean and coastal shared natural resources:Chapter 2.2 provides an assessment on the risks of shifting open-ocean fish stocks in the Pacific region due especially to ocean warming. It focuses on the challenges in governance and collective management across borders, with a view of potentially high consequences for global food security, the stability of entire regions and countries, and livelihoods at local scales.

- Agricultural commodities and food security:Chapter 2.3 assesses the cross-border and cascading risks of climate change and adaptation decisions in the production and trade of key agricultural commodities (maize, wheat, rice and soybean) in global food supply chains.

- Industrial supply chains: Chapter 2.4 assesses how transboundary climate risk cascades via global industrial supply chains, making local risks global relatively quickly. It also explores gaps in integrated risk assessment across global supply chains, and a lack of information sharing and coordinated decision making across stakeholders that is critical for building resilience.

- Energy and sustainable energy transformation: Chapter 2.5 presents an analysis of climate change and extreme weather events on interconnected energy networks across borders, and the cascading risks to disrupted energy supplies on people. Further, it presents developments in policies for building more climate resilience in interconnected energy networks.

- Finance: Chapter 2.6 assesses transboundary climate risks in global financial systems, with a specific focus on risks to foreign direct investment (FDI). It explores climate risk assessment methods to better integrate these risks in international financial networks.

- Human health: Chapter 2.7 assesses climate change risks on the accelerated geographical spread of some vector-borne diseases by expanding the habitat for the vectors and by inducing human mobility. It looks at how adaptation responses in one country, such as enhanced climate-sensitive disease surveillance and control, can help neighbouring countries adapt to climate change and even reduce the global risk of disease spread.

- Human mobility: Chapter 2.8 takes a deep dive on transboundary climate risks and international labour markets, specifically looking at seasonal and guest worker arrangements and the indirect risks to the international flow of remittances.

- Livelihoods: Chapter 2.9 explores the multiple ways that climate change risks and adaptation responses can trigger cross-border risks to different livelihoods, and takes a deep dive on the implications for pastoralism in the Sahel region.

- Wellbeing: Chapter 2.10 explores transboundary climate risks to wellbeing in different adaptation contexts. It analyzes the potential opportunities and challenges for a just transition in the context of transboundary climate risks, including how adaptation responses to equity issues can displace risks from one community or sector to another.

To explore the transboundary climate risks and their respective case studies in more detail please refer to pages 29-96 of the report.

Key Messages

The insights emerging from this report demonstrate a blind spot in climate policy: complex climate risks that are transboundary and cascading. These risks represent a shared adaptation challenge and a global responsibility.

- Transboundary climate risks, which are triggered by a climate hazard in one country, cross borders, continents and oceans to affect communities on the other side of the world. So do the consequences of some adaptation actions.

- In a world that is increasingly interconnected, these risks are transmitted through shared natural resources and ecosystems, trade links, finance and human mobility.

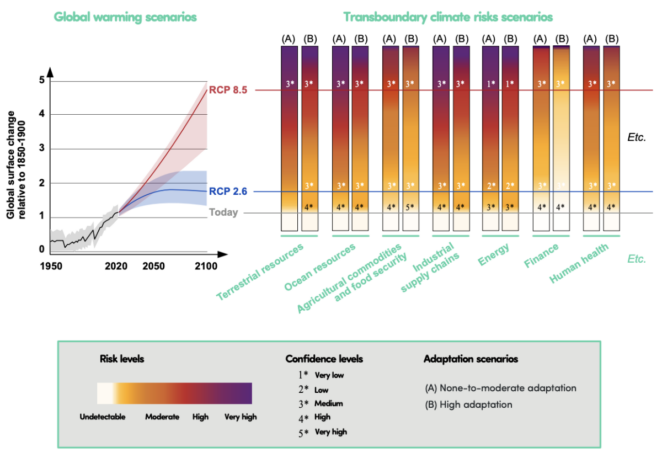

- Transboundary climate risks are expected to increase as global warming accelerates to threaten entire societies and economies.

- No country is immune: transboundary climate risks can affect any country, at any time, regardless of its level of development. They combine with non-climate drivers such as poverty and conflict to undermine our collective wellbeing.

- Transboundary climate risks have the greatest impact on the poorest and most vulnerable people, exacerbating inequities and the root causes of their vulnerability.

- Evidence shows that transboundary climate risks are a global concern, yet the international, regional and local mechanisms to adapt to climate change are not yet equipped to meet this common challenge.

- We need a global response to transboundary climate risks if we are to build collective resilience to climate change.

Rising to the challenge: the next steps

National, regional and international efforts to respond to climate change cannot succeed without understanding and addressing transboundary climate risks. These profound risks compel us not only to rethink climate risk, but also to expand the way in which we manage climate risk and plan adaptation.

The insights emerging from this report challenge a narrative that has long been embraced in climate policy: that adaptation is a local concern, while mitigation is a global responsibility. Rather, it tells us that climate change risks and adaptation responses can no longer be framed solely as domestic issues: they must also be seen as a regional-to-global concern. This in turn raises multiple governance challenges, as well as requires the development of new methods to assess complex risks to better inform climate change adaptation policy and planning.

The report sets out ways to reframe climate risk, adaptation policies at multiple scales, and international cooperation on adaptation, shifting from the local to the global. It outlines four potential areas for progress:

- Opportunities for innovative research on transboundary climate risk

- There has been little in-depth scientific research to date on the nature of transboundary climate risks, their timescales, their transmission modes and related adaptation policy responses. Similarly, there have been few – if any – robust assessments of both transboundary risks and the potential cascading, cross-border effects of adaptation decisions (particularly at the national level); or the relevant governance arenas and mechanisms.

- The design of indicators to track transboundary climate risks

- The tracking of transboundary climate risks is a new scientific challenge, and studies to either scope or address these risks are only beginning to emerge. However, the literature on tracking adaptation progress at the global level is more established and explores some approaches, such as the Global Adaptation Progress Tracker (GAPTrack) methodology, that hold some promise for the tracking of transboundary climate risk.

- Research on the future of transboundary climate risks based on scenarios and foresight exercises

- There is some knowledge on specific topics that are relevant for transboundary climate risks. However, we still lack a comprehensive and global-scale understanding of the level of transboundary climate risks we face today, and those we could expect in the future under various climate scenarios.

- Assessing such a “big picture under climate change” raises important methodological challenges, especially in identifying comparable indicators, metrics and other information across diverse transboundary climate risks and in considering future climate and non-climate trends together. In such a context, approaches based on expert judgement exercises could add value.

- The use of foresight and scenario exercises also to characterize policy pathways to address transboundary climate risks

- The “adaptation pathway” approach that has emerged over the last two decades offers a practical way to think about how to organize actions through time and, therefore, drive robust adaptation policy.

The report confirms that cooperation is vital for the management of transboundary climate risks, as seen in its various case studies. An approach based on cooperative solutions to transboundary climate risks would be more equitable, more just – and have far more chance of succeeding – than today’s country-centric approach. Despite the profound dangers posed by transboundary risks, they offer opportunities to build our collective resilience and to share the benefits of coordinated adaptation activities worldwide

To explore the solution space to managing transboundary climate risks, next steps, and knowledge gaps in more depth please refer to pages 97-113 of the report.

- New risk horizons: Sweden’s exposure to climate risk via international trade

- Multilateral adaptation finance for systemic resilience: addressing transboundary climate risk

- Impacts of climate change on global food trade networks

- Questioning the scientific feasibility and policy relevance of assessing transboundary climate risks

- Rising to a New Challenge: A Protocol for Case-Study Research on Transboundary Climate Risk

Comments

There is no contentYou must be logged in to reply.